Behind the Numbers: A Traditional Church Faces a New America

A Discussion for Church Leaders on the Decline of Weekly Church Attendance and Possible Strategies for Growing Your Place of Worship

Hank Bitten

The free exercise of religious beliefs is written into our constitution and has been part of the framework of our democratic society and American identity since the Pilgrims arrived in 1620. The principle of the separation of church and state prevented America from having a religious institution or denomination supported by the state, it has enabled the proliferation of houses of worship, the establishment of colleges to train clergy, the dissemination of religious beliefs into our culture through art, literature, and music, and prayers in public places. Religious beliefs and the practices of denominational churches are part of the tapestry of America.

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” (First Amendment)

This is clearly evident in the First and Second Great Awakening, the Sunday School movement, and the missionary zeal in the 19th century to convert people to the Christian faith. The names of Jonathan Edwards, George Whitfield, Charles and John Wesley, Francis Asbury, Billy Sunday, Billy and Franklin Graham, Dwight Moody, Phoebe Smith, Mary Baker Eddy, James Dobson, Tim Keller, Oral Roberts, and Pat Robertson are just a few names that are part of several high school history textbooks.

In the first two chapters of the dissertation, “Behind the Numbers: A Traditional Church Faces a New America”, Rev. Larry Vogel, presents us with a turning point in the first two decades of the 21st century that is an opportunity for discussion, debate, and discernment. The dissertation provides a sociological, anthropological, and theological perspective that is insightful in how evidence is used to support a claim or thesis.

The data from the U.S. Census Bureau presents a vision of America that is as influential today as Jean de Crèvecoeur’s “Letters from an American Farmer” were in 1782. Crèvecoeur tried to describe the ‘new American’ as industrious and religious. The experiences of living during and after the American Revolution changed the colonists from Europeans to Americans. The ‘new American’ following the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 is from global origins and the ‘new American’ is Hispanic, African, and Asian.

By analyzing the census data in this dissertation, high school students will be able to make a claim regarding the importance of religion in American by 2050, the impact of immigration on society, the consequences of a society that is changing over time, and make predictions for the future. In a Sociology class, students can also survey their own community and compare the data with the national data in the U.S. Census.

“As for ethnicity, 61.6% of the US population is White alone (204.3 million), a decline from 223.6 million and 72.4% in 2010. Blacks who self-identified without any other racial combination increased slightly in number between 2010 and 2020 (from 38.9 to 41.1 million), but declined very slightly as a percentage of the population (from 12.6% to 12.4%). The Asian alone population of the US increased both numerically and proportionately. In 2010 14.7 M (4.8%) Americans identified as Asian alone. In 2020 that number swelled to 19.9 M (6%).” The Asian population is projected to more than double, from 15.9 million in 2012 to 34.4 million in 2060, with its share of nation’s total population climbing from 5.1 percent to 8.2 percent in the same period. (p. 58)

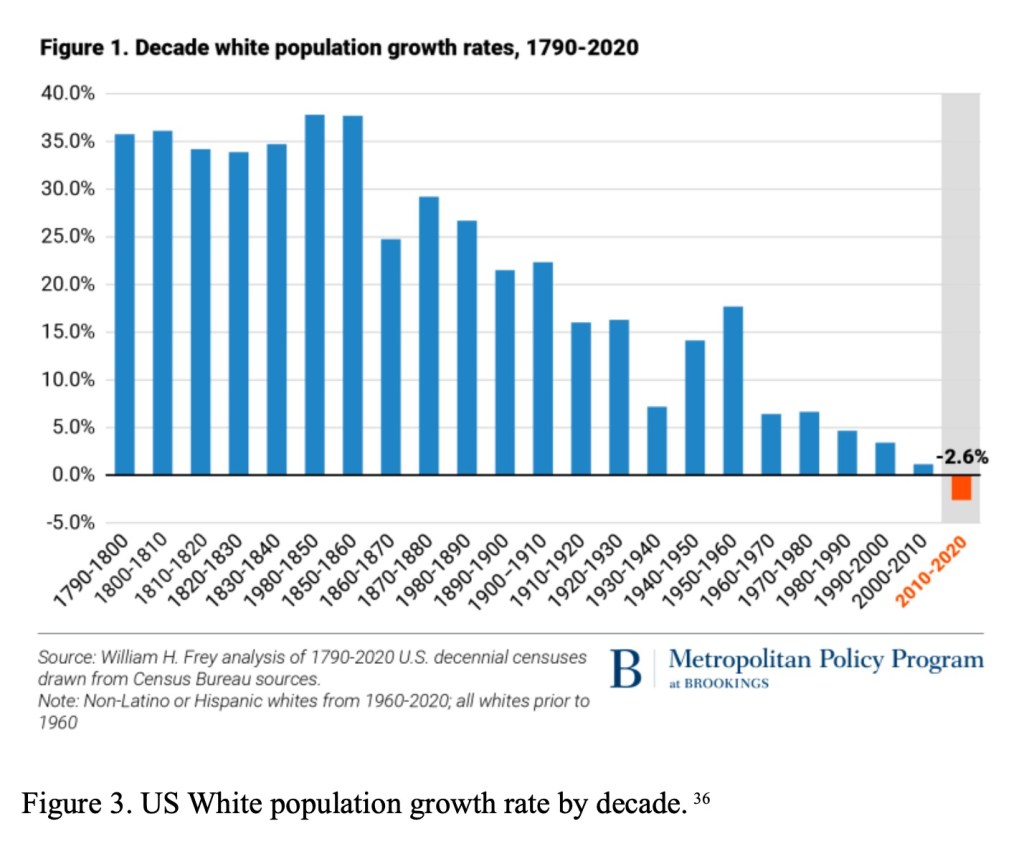

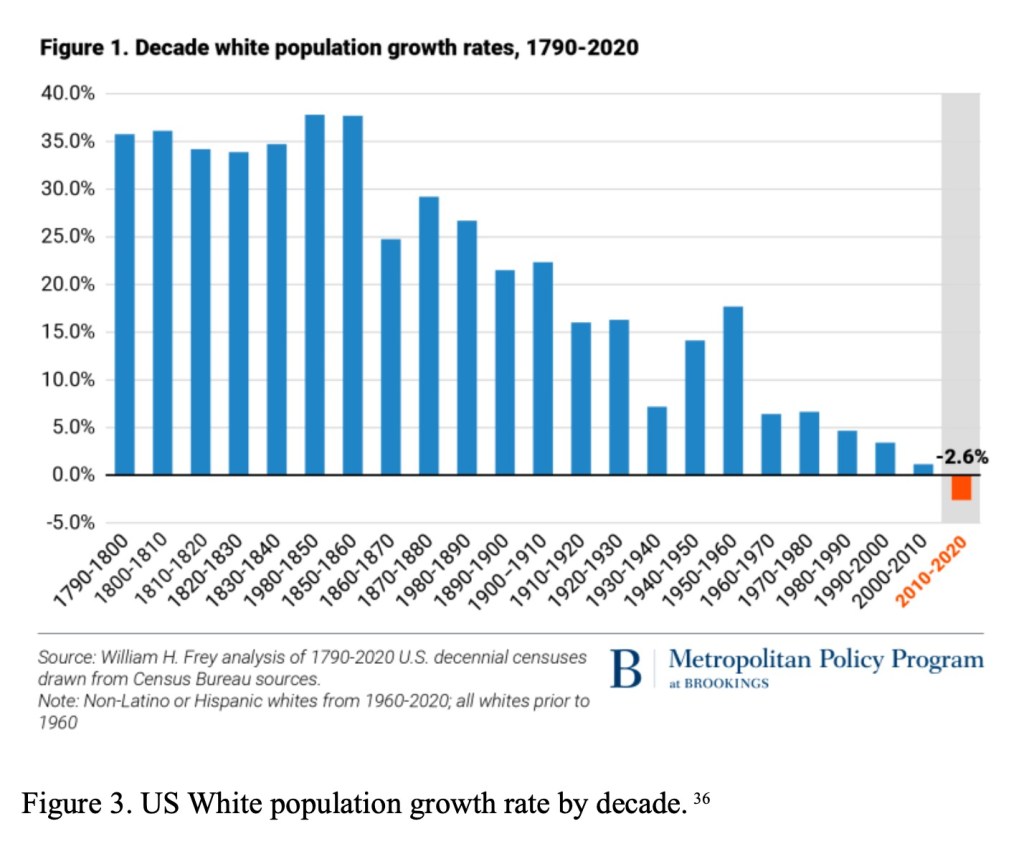

In the table below, the majority population in the United States declined 11% in ten years from 2010-2020. Will this trend continue to fall another 10% or will it be greater than 10% in this decade?

The demographics of what is happening to the religious beliefs of the ‘new American’ are important to our culture, economy, education, families, and government. Religion is perhaps the largest service industry in the United States with more than 100 million people attending worship regularly. The number of subscribers to weekly worship experiences is declining but this change is likely disguised as the ‘new American’ still believes in a supreme deity but expresses this belief differently than the way Crèvecoeur’s ‘American’ did. The insights in “Behind the Numbers: A Traditional Church Faces a New America” encourages the debate by church leaders and clergy. The analysis of the data provides a perspective of what life will be like in the United States at mid-century. Some will see this as an opportunity and others as a threat.

To begin our inquiry into the data, examine the population profile of the top ten states with the highest immigrant populations. (pp.66) Half of these states are in the Boston-New York-Philadelphia-Baltimore- Washington, D.C. corridor. A third of these states are in the western region of the United States.

One of the striking observations in the census report is that these changes have occurred after 2000.

“The continued growth of the US population is due to immigration rather than to immigrant birth rates. All-in-all, the foreign-born US population in 2018 was nearly 14% of the total US population and their second-generation children were an additional 12.3% of the total population. This means that fully 25% of the current US population is the result of immigration and that the changing racial-ethnic profile of the US is due almost entirely to immigration in recent decades. As Taylor puts it: “Immigration is driving our national makeover.” (p. 67)

As you review the data in the graph below, consider the implications of this decline in your community and state.

Here are some questions to ask regarding this data?

- Will these demographic trends continue on the same trajectory over the next three decades or escalate?

- Will external events (i.e., climate, artificial intelligence, economic conditions, etc.) have a direct effect on immigration trends?

- Will the immigrant population move to other states as they have in the past?

- As the immigrant population of 2020 ages, how will this influence the ‘new American’ identity?

- As immigrants assimilate into American culture, will they be influenced by the religious institutions in America?

The Census Bureau predicts that the trend toward racial-ethnic diversity will continue: The non-Hispanic White population is projected to shrink over coming decades, from 199 million in 2020 to 179 million people in 2060—even as the U.S. population continues to grow. Their decline is driven by falling birth rates and a rising number of deaths over time as the non-Hispanic White population ages. In comparison, the White population, regardless of Hispanic origin, is projected to grow from 253 million to 275 million over the same period. (p. 236)

Dr. Vogel’s thesis claims that “the underlying support and stimulus for Global Christianity’s surge is the Bible translated into the vernacular. The Bible in whole or in part is available in over 1500 languages, including more than 650 African tongues. With the Bible in their own tongue, Christians in Africa and throughout the globe “can claim not just the biblical story, but their own culture and lore in addition.” (p. 82) However, his thesis also raises the counterargument that the Millennial generation (birth years 1981-1996) is leading the shift away from organized religion, specifically, Christian denominations. According to the Pew research from 2019, 40% of the Millennials (also Generation Y) identify as unaffiliated with 9% claiming a faith other than Christianity. The trend for Generation Z (birth years 1996-2010) will likely be higher.

The perspective of Dr. Mark Chaves of Duke University (and high school student of the author of this article), is that America will likely continue its religious identity in this century. The diversity of the American population will lead to changes, notably that non-Christian beliefs also lead to eternal life. Church membership and worship practices will likely change. A new subculture within the religious and worshipping population may emerge in the 21st century. The ‘new American’ will likely continue helping others in need by donating food, working in a soup kitchen, providing assistance after a disaster, building homes for the homeless, as the volunteer spirit will likely continue throughout this century. But this ‘new American’ may also be influenced by social media and artificial intelligence. Engage your students in exploring answers to these questions and possibilities.

George Hawley of the University of Alabama presents a strong counter argument regarding the demographics of the denominational church in 2022. He cites that 23 percent (almost one-fourth) of the population affiliated with a Christian denominational church are over the age of 65. He also observed that only 13 percent who attend church regularly are under the age of 30. This is not sustainable beyond 2050. Non-Christian religious traditions increased from 5% percent to 7% since 2010. In terms of actual numbers, 13 million Americans identify as atheists and 33 million or 10 percent) have no particular religious affiliation. To place this in perspective, the populations of 49 states are less than 33 million people. The population of Texas is 31 million.

To add a second layer of analysis to our scaffold is the research of the Barna Group which used three factors in determining affiliation with a Christian Church.

- Christian identity with a denominational church

- Regular worship attendance

- Placing faith as a high priority

The data reports that 25% of the American population of 330 million people are practicing Christians. In 2000, the number was 45%! (p. 113) Although weekly church attendance continues to decrease in both Protestant and Roman Catholic churches, the diversity of Roman Catholic congregations appears positive, especially if the United States will continue as a Christian country. “Nearly 40% of Catholic churches are either predominantly or very much non-White. In 2014, The Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) study of RCC parishes, 323 out of 846 responding parishes could be identified as multi-cultural parishes.” (p. 131)

By using the data below, ask this question: ‘Why is Roman catholic weekly attendance decreasing in the first quarter of this century and Protestant weekly attendance showing a slight increase?’ (Note: the years on the y axis appear to have 1983-1986 reversed with 1995-1996)

Having reviewed the data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the data on individuals who are unaffiliated with a church denomination, consider the following observations regarding strategies for your individual need. One size does not fit every situation because of locations in rural, suburban, and urban areas, income and population demographics, and the fact that the research in the dissertation applies to Lutheran church experiences over the past 50 years. However, the research and data apply to most church denominations and readers should consider selective ‘talking points’ for their individual experience or need in the context of the catholicity of the Christian church, which is broader than the introspective doctrinal definitions of clergy or a religious organization.

Observations on the decline of Lutheran church populations (pp. 154-174)

Chapter 3 of the dissertation analyzes the demographics of several denominational churches and non-denominational churches. The Lutheran Church (LCMS) is presented as a case study for empirical and comparative evidence. Of the nearly 6,000 LCMS congregations, about 20% have fewer than 25 people attending weekly and 75% have fewer than 100 attending weekly. The picture for the Mid-Atlantic region, despite LCMS congregations in about two-thirds of all the region’s counties. New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania all experienced steady decline from 1970 to 2010. Total LCMS membership was a little over 100,000 in the region in 2010, about half of its membership in 1970.101 (p.187) Lutherans are not, on average, particularly committed to their faith. They are less diverse than any other group and they are much older than the overall population—with the LCMS even older than the ELCA. (p. 216)

The LCMS statistics for the South Atlantic region are more positive. Between 1970 and 2010, six of its eight states grew in LCMS membership. Maryland lost about 10,000 of the 30,000 members, the largest loss in the region. South Carolina membership grew by about 1,000 (nearly 50%). Virginia added over 5,000 (also about 50%). Florida added about 50%, or 20,000 members. Georgia added about 30%, around 2,500 members. And North Carolina added about 50% or 7,000. Only Georgia and North Carolina added members during the final decade of the period, from 2000 to 2010. (p. 189)

Baptists are in decline as a percentage of the United States (from about 20% of the United States in 1973 to around 14% in 2014). But the retention rate for Baptists is quite strong at about 78% and the total number of Baptists remained about the same.

The United Methodist Church now claims less than 4% of the population and far smaller numbers are active members. Only the African Methodist Episcopal branches of Methodism are growing. The UMC is 94% non-Hispanic White, has smaller than average families, with low retention rates of about 40% of those raised Methodist remaining in the church.

Mormon families enable the Church of Latter-Day Saints to remain strong. Mormon women with an average of 3.4 children compared to the national average of 2.1. They are also more likely to be married.

• “The retention of baptized and confirmed youth is a key area on which to focus.”

• “The number of child baptisms and adult converts have decreased together in a remarkably similar pattern.”

Baptisms are important for growing the church at the parish level. If infant or child baptism is considered important, then the activities organized by the congregation should consider intergenerational opportunities for children, parents, and grandparents to continually support the baptized child in faith through the life of the local congregation.

The connection between marriage, parenthood, and religiosity is well established. This effect is particularly pronounced for men, who are more likely to return to religion upon getting married or becoming a father. (pp. 179-80) The U.S. Census data reports that the unmarried population of the United States is approaching 50% of all adults. It is important to acknowledge the spiritual needs of this large and significant segment of the population. Marriage and parenthood are “critical for the survival of a church,” but only when children remain in the church as they become adults. (p. 185)

The LCMS ought to be fostering both internal and external growth by engaging in solid teaching about the gifts of marriage and children, so that the LCMS would grow as individual members marry, faithfully live according to the Word of God together, bear children, and bring them up as baptized disciples who learn to keep all that Christ has given to His church. In addition, the LCMS and its congregations ought to be vigorously engaged in evangelizing those who do not know Christ. (p. 254) “Congregations must be safe places for young people to wrestle with life and faith.” (p. 255)

A second strategy considered in the dissertation is stewardship education. In planning this, church leaders need to be aware of how to optimize income, the number of single parent households, extended family living arrangements, budgeting, and how to minimize debt. A serious threat to families and the local congregation is poverty, loss of income, and overspending. Churches effectively ask for contributions and some make an effort for their members to tithe. Unfortunately, few churches have the resources to help people with unexpected situations such as a loss of income, medical situation, or disability. In addition, young families and single parents have the high costs of child care, child care, and a plan to save and invest. Developing a financial mindset is an opportunity for local congregations to assist people in a practical way.

A third observation that Dr. George Hawley noted is that churches that demand more of their members have outpaced churches with minimal expectations. (p. 183) In this context, he suggests that small groups were equally effective regardless of congregational size. He also observed that contemporary worship music and styles are less of an appeal to young adults than to middle-aged adults. (p.185) One of the barriers to congregational growth is the complacency of its members. The model of the first century church should be considered by 21st century church leaders by making an effort to engage the entire spiritual community in serving others and growing together. As populations migrate from one community to another and as individuals experience anxiety and mental stress from feeling alone, the local church community needs to utilize its human resources to assimilate members into their community, culture, and place of worship.

Perhaps the two most effective strategies are the reputation of the church in the community and the personal contact that church leaders have with members and visitors through phone calls and interactive conversations. (p. 185) “Over these last two chapters, we saw that there are three variables that are correlated with strong denominations: the propensity to marry young and have large families, racial and ethnic diversity, and the percentage who claim that religion is very important to them.” (p.229)

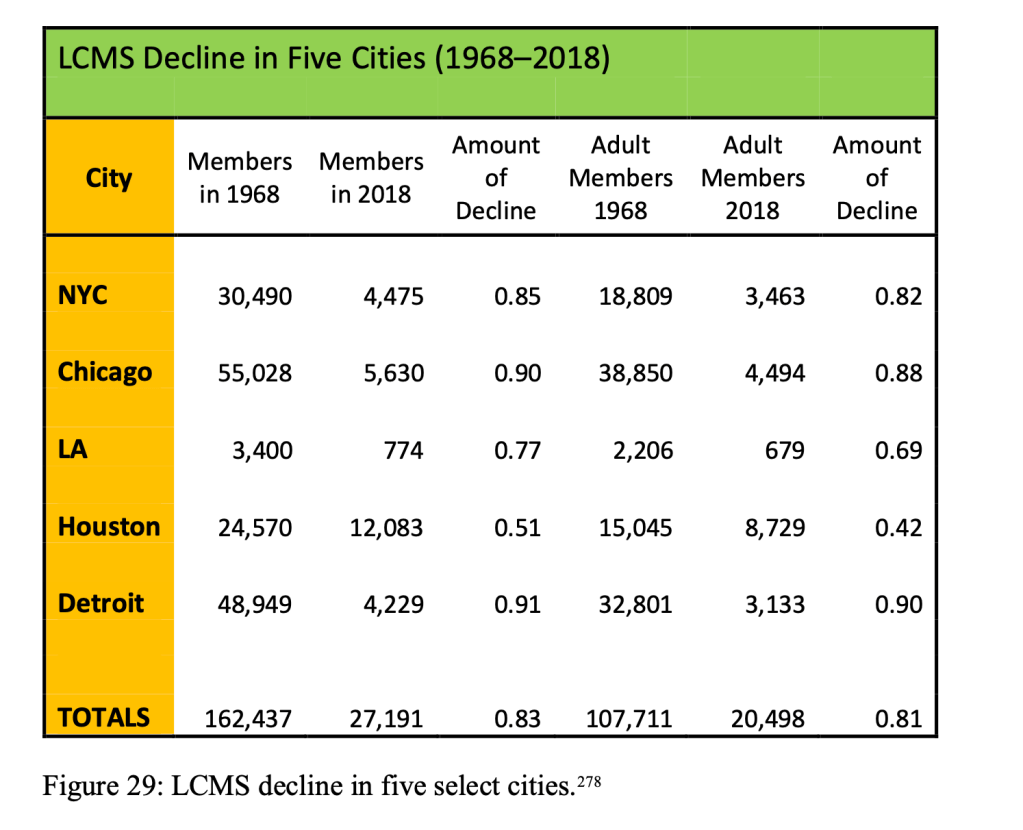

To summarize the fifty-year data presented in Figure 29, LCMS baptized membership in the five cities in question declined, overall, from 162,437 souls to 27,191. The LCMS has only slightly more than 15% as many members today as five decades ago in those cities. That is a decline of 83%! Two of those cities, Chicago and Detroit, lost population, but not nearly on the level that the LCMS declined. Detroit’s population loss was the most dramatic. Detroit and Chicago had strong populations for most of the 20th century. Its 1970 census population was 1,511,482. By the 2020 Census, Detroit’s population was only 639,111, a loss of 58% of its population (p. 239). The decline in New York City follows a similar pattern. Lutherans began worshiping in New York City in 1643 and in the 19th century, New York had a vibrant Lutheran and Protestant population and the first Thursday in June was designated as a local holiday in commemoration of the first Sunday School in 1838. As recently as 2005, this became a city-wide school holiday! This is a reminder that populations change as a result of the economy, crime, or political changes and that population changes affect schools and churches.

LCMS presence on the coasts is in sharp decline while the coastal US remains densely populated with 40% of the US population living in counties adjacent to either the Pacific or Atlantic coasts. (p. 244) The local church in decline needs to consider the changes in the diversity of the American population, especially in the top 25 states identified on the map below. Changes to worship styles, a visible presence in the community, hosting invitational events each have value but they are short term applications for sustained growth and connections with people.

The events of the next 15 years (2025-2040) will continue to support population migrations as climate changes cause coastal flooding, food insecurity, wildfires and heat related deaths. The influence of artificial intelligence will challenge church doctrines and civic understanding. Local and state governments may become more influential in coping with poverty, education, and the assimilation of new populations. The costs and scope of the anticipated problems in this century are likely beyond the power of national governments to solve which leads to my conclusion that this is an opportunity for the global church. The model presented in the dissertation by Dr. Vogel deserves discussion and debate as it supports the model of the first century church at a time when the Roman Empire was declining. If historians select 1975 as the beginning of the decline of American hegemony, then we are already a half-century into a turning point in world civilization and history.

The conclusion of Dr. Vogel’s thesis speaks to us as a fire bell calling the first alarm to a five-alarm fire at a church that is becoming disconnected to the population. The church in every local community needs to connect with a diverse, and perhaps disconnected, population. This is the purpose of the churches in our communities.

Chapter 4 of the dissertation provides an important analysis and historical overview of the catholic role of the Christian Church. This chapter is worth reading as the evidence clearly supports the worldview of the Christian Church in connecting with the population changes in the 21st century. A summary is not practical because of the comprehensive analysis offered.

“The church’s catholicity—its inclusiveness—involves different socio-economic groups. When Jesus says that we will always have the poor with us (Matt. 26:11; John 12:8), he is not inviting his disciples to neglect care for the poor in favor of gifts to him. Rather, he contrasts the beauty of a gift given at an opportune time (the woman’s anointing of her Lord) to a constant concern for the poor. How right it is for the Church both to adorn its worship with the most beautiful sights and sounds, and to do so all-the-while regularly seeking ways to include and to assist those who struggle with poverty and other immediate needs. To take catholicity to heart as a Synod would therefore require a sober assessment of our abandonment of the poor, whether rural or urban, although special attention herein has been given to cities.” (p. 377)

The conclusion in Chapter 5 is also worth reading regarding the acceptance of all people in a diverse community. If we use 1975 as a pivotal year for marking the end of the “American Century” we will recognize that every country in the world has experienced changes as a result of population, economics, technology, and spirituality. Fernand Braudal, a French historian and leader at the Annales School, developed a model for understanding how change occurs over time in human societies. We understand history differently in each era. The lens or perspective of understanding life on our planet and civilization may be understood through political, geographic, economic, and cultural interpretations. The Christian church can learn from this model and embrace it by connecting with the diversity of people on its doorstep. The lens of the 21st century is experiencing a change in direction because of the diversity of populations and the sharing of ideas, resources, and the need to address global problems. Church leaders and church members need to embrace this as an opportunity.

I leave you with this thought by Dr. Larry Vogel:

“Segmenting the church by generational groups not only is potentially problematic in its effects on families. It is also contrary to the horizontal catholicity of the faith. Christianity is for all people, not only in terms of ethnicity or cultural group or language, but also for all ages. For the tiniest infant and the aging woman with Alzheimer’s.” (p. 371)

https://scholar.csl.edu/phd/146/

Behind the Numbers: A Traditional Church Faces a New America

Larry Vogel, Concordia Seminary, St. Louis

Date of Award: 5-19-2023

Document Type: Dissertation

Degree Name: Doctor of Philosophy (PhD)

Department: Practical Theology

First Advisor: Richard Marrs

Abstract

The dissertation examines membership data for The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod (LCMS) from the mid-1970s to the present. It considers the analysis of LCMS decline by two scholars, George Hawley and Ryan MacPherson, who independently proposed that LCMS membership decline was internal in causation due to diminished birthrates and fewer young families. While acknowledging the reality of such internal decline, this dissertation argues that the lack of external growth is a greater cause for LCMS decline. Its lack of external growth is due primarily to the racial and ethnic homogeneity of the LCMS and its failure effectively to evangelize the increasingly diverse American population. This indicates a theological weakness: a failure to teach and emphasize the catholicity of the church adequately in LCMS catechesis and dogmatic theology.

Recommended Citation

Vogel, Larry, “Behind the Numbers: A Traditional Church Faces a New America” (2023). Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation. 146. https://scholar.csl.edu/phd/146

INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1

WHAT STARTED AT PENTECOST……………………………………………………………………………. 1

The Mystery of Faith ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 1

Two Ways of Growth—Handing On and Handing Down ………………………………………. 2

Marks and Mission …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3

Movement toward People ………………………………………………………………………………………. 4

THE THESIS ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..7

Support for the Thesis……………………………………………………………………………………………… 7

THE APPROACH……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9

CHAPTER ONE…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 12

DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE IN THEORY, REALITY, AND APPLICATION ………………… 12

THE DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION—A GLOBAL PHENOMENON…………………………. 12

Demographics Defined ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 12

The First Demographic Transition ………………………………………………………………………… 13

The Second Demographic Transition…………………………………………………………………….. 17

Cause of the Demographic Transition ………………………………………………………………….. 23

US DEMOGRAPHICS ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 24

EFFECTS OF THE DT ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 27

Primary Effects: Declining Births, Increasing Age………………………………………………… 27

Secondary Effects: Changes in Female Life Patterns and Family Formation …………………… 32

RESPONSES TO DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE……………………………………………………………… 40

Responses to the Demographic Transition: A Survey…………………………………………….. 41

China’s Response to Demographic Transition……………………………………………………….. 42

Brazil’s Response to Demographic Transition……………………………………………………….. 45

The European Response to Demographic Transition …………………………………………….. 47

The North American Response to Demographic Transition…………………………………… 50

THE CHANGING DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE……………………………………………………………… 57

New America: Older and More Female,……………………………………………………………………. 58

New America: Greater Diversity……………………………………………………………………………….. 58

CHAPTER TWO …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 68

THE DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGE AND RELIGION………………………………………………….. 68

DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE AND RELIGIOSITY—A WORLD TOUR …………………………….. 68

DT and Religion in Asia ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 68

DT and Religion in Latin America………………………………………………………………………………. 74

DT and Religion in Africa …………………………………………………………………………………………… 78

DT and Religion in Europe …………………………………………………………………………………………. 85

DT and Religion in the United States: Six Trends……………………………………………………… 92

The Millennial Challenge…………………………………………………………………………………………… 96

The Challenge of Multiethnic America ……………………………………………………………………. 100

The Challenge of Family Decline………………………………………………………………………………. 102

The Challenge of Income Inequity …………………………………………………………………………… 104

Conclusion: DT and Religion in America…………………………………………………………………. 106

DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION AND DECLINE IN AMERICAN CHRISTIANITY………..108

Rise of the Religiously Unaffiliated and the DT……………………………………………………… 109

The Healthiest Churches………………………………………………………………………………………….. 118

THE NEW AMERICA IN THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH…………………………………….. 123

A Church in Crisis: Flight from the Roman Church ………………………………………………… 125

A Church’s Hidden Strength: The Diversity of American Roman Catholics…………… 127

THE NEW AMERICA IN THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN AMERICA ……………………. 133

A History of Struggle ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 133

Growth in the PCA through Doctrinal Fidelity and Outreach …………………………………. 142

Reflection and Redirection ………………………………………………………………………………………. 144

CHAPTER THREE………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 153

A CLOSER LOOK AT THE LCMS DEMOGRAPHIC DILEMMA ……………………………………. 153

DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION AND THE LCMS ……………………………………………………….. 153

From Growth to Decline …………………………………………………………………………………………… 153

The Graying of the LCMS …………………………………………………………………………………………. 159

ADDRESSING LCMS DEMOGRAPHIC DECLINE: RYAN MACPHERSON AND GEORGE HAWLEY …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….161

Ryan MacPherson…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 162

George Hawley………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 176

LCMS—Demographic and Social Change ……………………………………………………………….. 177

District-Level Trends………………………………………………………………………………………………. 202

Demography, Culture, and the Decline of America’s Christian Denomination………205

MACPHERSON AND HAWLEY: AFFIRMATION AND CRITIQUE……………………………… 218

Affirmation……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 219

Critique ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 223

THE DEPTH OF THE DEMOGRAPHIC DILEMMA …………………………………………………… 233

The Constancy of the LCMS Demographic Profile …………………………………………………. 235

A Homogeneous Synod and Growing American Diversity……………………………………… 235

Population Migration and the LCMS—Flight from Urban America ……………………… 238

Breaking Down the LCMS Dilemma ………………………………………………………………………… 243

What’s Going On? Failure to Connect with America’s Changing Demographic Profile ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………243

“Why Is It Going On?” Families, Homogeneity and Racialization …………….……….….244

“What Ought to Be Going On?” Plotting a Future for the LCMS …………………………… 254

“How Might We Respond?” Reflection on the LCMS Demographic Profile…..……… 256

CHAPTER FOUR……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 257

CATHOLICITY AND THE CHURCH …………………………………………………………………………. 257

HOLY SCRIPTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 263

The Hebrew Scriptures…………………………………………………………………………………………… 264

The Gospels…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 266

The Acts of the Apostles…………………………………………………………………………………………. 268

Epistles of Paul and Hebrews…………………………………………………………………………………. 274

Catholic Epistles and the Apocalypse …………………………………………………………………….. 280

TRADITION……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 286

Catholicity in the Early Church………………………………………………………………………………. 286

Catholicity in the Medieval Church ……………………………………………………………………….. 293

The Reformation and Catholicity…………………………………………………………………………… 300

The Synodical Conference and the LCMS ………………………………………………………………. 310

Catechisms ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 313

Doctrinal Theology…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 325

CATHOLICITY AND THE CONTEMPORARY CHURCH …………………………………………… 340

Lamin Sanneh…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 341

Soong-Chan Rah…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 350

Leopoldo A. Sánchez M. …………………………………………………………………………………………. 359

SUMMARY: CATHOLICITY IN SCRIPTURE AND TRADITION……………………………….. 366

CHAPTER FIVE ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 369

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS …………………………………………………………. 369

THE NEW AMERICA AND THE LCMS: ACKNOWLEDGING THE PROBLEM………… 369

The Demographic Dilemma—Transition …………………………………………………………… 370

Implementing Merits of MacPherson and Hawley……………………………………………… 370

Catholicity Ignored………………………………………………………………………………………………. 373

TAKING CATHOLICITY TO HEART: REMEMBERING THE FORGOTTEN…………… 374

The Work of Catholicity……………………………………………………………………………………….. 380

Race—an Ongoing Challenge……………………………………………………………………………….. 383

Challenging Political Polarity ………………………………………………………………………………. 387

Thoughts on Further Research ……………………………………………………………………………. 389

Learning Catholicity …………………………………………………………………………………………… 390

APPENDIX ONE……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 394

APPENDIX TWO…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 395

AMERICAN GENERATIONS ……………………………………………………………………………….. 395

APPENDIX THREE………………………………………………………………………………………………. 396

BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 397

VITA ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 455

Talking Points for Church Leaders:

- “The conclusion of this research is that the LCMS will not be able to engage in effective mission outreach unless it forthrightly addresses the changing demographic reality of the United States. There is no reason for the LCMS to forsake its constitutional objectives such as promoting doctrinal unity while avoiding unionism and promoting mission. But when we give minimal attention to the doctrine of catholicity are we meeting our second objective? Will we take to heart Leo Sanchéz’s reminder “that, in light of the increasingly ethnocultural diversity of our future, unity and mission language in synodical ecclesiology will need to be broadened and deepened critically and constructively with language that fosters the catholicity of our Synod’s identity and task in the church, the world, and the marginalized areas between the two”? It is essential for the LCMS to understand that to take its second objective to heart requires the Synod fully to appreciate and to teach that catholicity is of the esse of the Church—it is an element of identity. And, as such, it implies a task: giving attention to places and people we have largely forgotten.” (p. 376)

How do we understand ‘catholicity’? Is it catholicity with Lutherans, all Christian denominations, non-Christian faiths? Is our understanding of ‘catholicity’ limited to ages, sexual or gender preferences, people without disabilities, language, or mental health? Does ‘catholicty’ mean our church needs to accept all people without any restrictions?

- The catholic calling to the LCMS means returning to cities and other places with non-Anglo populations. It means recognition of people of color throughout our communities. It means recognition that the poor will not be forgotten by God, nor are they to be forgotten by us. And it will require workers who can joyfully accept these tasks. (p. 379-80)

How can our congregation best serve the people of color in our community and support those living in relative poverty?

- The Census Bureau predicts that the trend toward racial-ethnic diversity will continue: The non-Hispanic White population is projected to shrink over coming decades, from 199 million in 2020 to 179 million people in 2060—even as the U.S. population continues to grow. Their decline is driven by falling birth rates and a rising number of deaths over time as the non-Hispanic White population ages. In comparison, the White population, regardless of Hispanic origin, is projected to grow from 253 million to 275 million over the same period. (p. 236)

How can the people of the local church become personally connected with the people in their neighborhood and in their church neighborhood?

- The LCMS ought to be fostering both internal and external growth by engaging in solid teaching about the gifts of marriage and children, so that the Synod would grow as individual members marry, faithfully live according to the Word of God together, bear children, and bring them up as baptized disciples who learn to keep all that Christ has given to His church. In addition, the Synod and its congregations ought to be vigorously engaged in evangelizing those who do not know Christ. (p. 254) “Congregations must be safe places for young people to wrestle with life and faith.” (p. 255)

How do we understand the recommendation to “be vigorously engaged in evangelizing those who do not know Christ?” How safe is our church for people who are wrestling with life and faith and not living according to the teachings of Jesus in the Holy Bible?

- In contrast with that, religiously unaffiliated American adults are now 26% of the overall population. This decline in religiosity is primarily at the expense of Christianity, not non-Christian religious traditions whose adherents have actually increased, from 5% to 7% of the US population over the decade from 2009 to 2019. (p.153) In the last five years alone, the unaffiliated have increased from just over 15% to just under 20% of all U.S. adults. Their ranks now include more than 13 million self-described atheists and agnostics (nearly 6% of the U.S. public), as well as nearly 33 million people who say they have no particular religious affiliation. (p. 156)

While the number of atheists and agnostics has certainly increased, Pew emphasized “that many of the country’s 46 million unaffiliated adults are religious or spiritual in some way. Two-thirds of them say they believe in God (68%).” And at least a small segment of them (10%) are interested in a religious institution.157 But the most striking result of the 2012 survey was its implication that this movement away from religious affiliation would increase, not decrease, because it was a phenomenon “largely driven by generational replacement, the gradual supplanting of older generations by newer ones.” (p. 158)

What is the significance of more than 1/3 of the population in the United States under the age of 30 having no religious affiliation with a local church or denomination? Can our local church ignore this population? How can we connect with them?